Two weeks before Christmas 2023, Richard Goodall and I headed up to Denstone College, near Uttoxeter in Staffordshire, to undertake the detailed voicing of their rebuilt chapel organ. David Mason’s already written in detail about this project, which involved rebuilding an old Copeman Hart installation.

The console is something of a monster, with 75 stops, so there was quite a lot to get through in the two days available. We completed it just before the end of term, in time for a final carol service.

Wrap-around organ – nice or nasty?

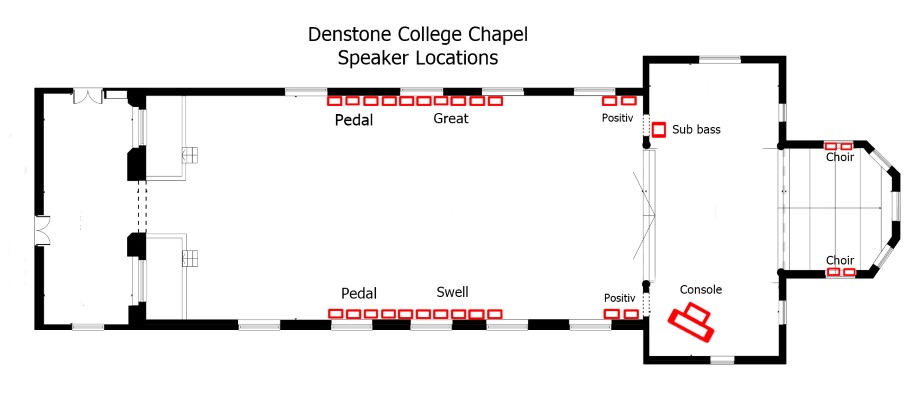

The loudspeakers had been mounted mostly on the high-up wall plates down the sides of the nave, with a group of ten on each side in the middle, four near the chancel arch, and four in the apse behind the choir. Because of their height, the ratio between reverberant and direct sound was nicely balanced at seating level, making it quite hard to pick out the sound from individual loudspeakers.

I’ve generally not been a lover of the wrap-around digital organ layout, which puts loudspeakers all around the nave, preferring in most cases an arrangement that more closely emulates a pipe organ case in a well-chosen part of the church. However, this installation led me to question my prejudice, and here is the way my thoughts ran.

Firstly, the Denstone chapel has a relatively short reverberation time, particularly when stuffed with hundreds of absorbent children. In buildings like this the level of direct sound from an instrument drops off quite noticeably as you get further from the sound source. It’s the inverse square law in action! (Direct sound level changes with the square of the distance from the source.)

In very reverberant buildings this is far less of an issue, because the reverberant sound level dominates once you get only a few metres away from the source, and this level is relatively unvaried throughout the building. One of the consequences of dryish acoustics, then, is that if the pipes or speakers are located in a single case, say on a west gallery, or in the chancel, you need a lot of power from the instrument for it to sound loud enough at the other end of the building. I witnessed this with the new pipe organ installation at Radley College (on the gallery at one end), where the level at the console is considerable, but seemed relatively modest at the far end of the nave.

Placing loudspeakers on both sides of the nave, at the front end of the nave, and in the choir, as was done at Denstone, largely counteracts the problem mentioned above. The sound sources of the main divisions are distributed nearish to the congregation, and there is plenty of power to support the main purpose—robust congregational singing. The organ sound is experienced at a similar level in most parts of the nave.

There is an argument for saying “we can do things differently with loudspeakers, so do what makes practical sense in the context, rather than trying to emulate the sonic effect of a historic compromise” One might surmise that pipe organ builders might have liked to do the same if they could have. Old Victorian chancel organs were notoriously poor at projecting sound into the nave, for example, and could be weak when supporting congregational singing. That’s why a lot of them are being rebuilt with nave singing in mind.

How to divide the divisions?

With 28 channels to play with, a scheme was needed to “build” the organ divisions. The Physis system has great flexibility in sound routing, with any stop being routable to almost any group of loudspeakers, in a variety of modes (stereo panning, C/C sharp, polyphonic, etc).

Rather than random “surround sound”, we arranged divisions of the organ rather like a split case on either side of the nave, with Great on one side, Swell on the other, and part of the Pedal on each side (see the diagram below). The Positive was placed at the front of the nave, near the chancel arch, and the Choir in the chancel apse. That way the Choir division fulfilled the function of choir accompaniment, also providing local support for congregational singing in the chancel when coupled to the Great or Swell. The Choir then sounded relatively subdued and blended further down the nave. (The school choirs currently sing mainly from the chancel area at Denstone.)

Can you really “voice” a digital organ?

It’s quite reasonable to question the term “voicing” when applied to digital organs.

The idea that we do voicing is often derided, when compared to the craft involved in making pipes speak nicely. I have come, though, to marvel at the transformation that can be wrought with an organ’s sound, using this particular system, after a day or two with a laptop and a pair of ears. To my mind the reason is partly that the system is based on sound synthesis rather than sampling, and there is a very clever set of high-level tools available to enable radical modifications to be made to the sound of basic voices.

With sampled organ systems, you are often rather stuck with the characteristics of the pipe sample you select. With synthesis-based organs, there can be more scope to alter the basic sound quite dramatically.

When we arrived at Denstone, the organ had only had a rough set up, simply to get things working and get the sound coming out of sensible places. It is not denigrating the system to say that it sounded bland, flat, and “electronic”, but that is where you usually have to start.

Having talked to the staff about their experience so far, we began by equalising all the loudspeakers, and balancing the level of the subwoofer with the main loudspeakers. Then, stop by stop, division by division we worked our way through the instrument, refining and beautifying the sound of each voice, so that each had its own unique character, and blended with other relevant stops in the division.

We had at our disposal controls that would vary the character of a flue stop from very stringy at one end to quite flutey at the other, from quite chiffy to plain speaking. We could introduce a degree of pipe-like instability to the tone, vary the amount of “squawk” on reed stops as they spoke, vary the pitch drift as a key was lifted, change the amount of air noise in the tone, and change the attack speed of notes. One was able to introduce realistic wind supply “sag”, touch sensitivity, and vary the tuning ensemble of individual voices relative to each other.

Polyphonic routing enables the notes of a particular voice to be routed to each of say six loudspeakers in turn, using an algorithm that ensures unisons don’t get sounded out of the same loudspeaker when multiple stops are drawn. This way the loudspeakers behave more like individual pipes than when the sound is panned stereophonically, and we used this form of routing mainly on the Great and Pedal. It created a rather direct effect, a bit like the front principal pipes on an organ case, whereas the Swell could be made to recede and blend better using other modes of routing, it was found.

Two days or two weeks?

I can well understand why Ernest Hart would have spent many weeks voicing his organs. Apart from the fact that he may have liked spending some time in the place and getting installed in the nearest village for a while, the process of making voicing adjustments on the original Bradford system was much more laborious than it is with a modern laptop and the Physis system.

Viscount has very cleverly abstracted the voicing controls from the nitty-gritty of low-level synthesis parameters, making it possible to arrive at meaningful sonic results extremely quickly. You can modify almost anything quickly and intuitively, it’s saved automatically, and the results are there the next time you turn the instrument on. That must account for quite a lot of the difference in time spent.

It may be a case of unreasonably blowing one’s own Trompette, but I honestly don’t think the organ at Denstone would have sounded much better after two weeks of work than it did after the two days we spent there. Refinements are inevitably going to be possible after living with the instrument for a while, and we look forward to hearing how the staff get on with it.

Initial impressions are very favourable. We left an instrument that started out sound boring, but ended up sounding remarkably characterful and life-like. The chaplain turned up half way through the second day saying that the organ sounded incredible — not sure what we’d done but it sounded like a cathedral in there now.

I’m a retired academic, with a background in music and audio engineering. I’m currently a consultant for Viscount & Regent Classic Organs, as well as being a freelance organist, including a role as organist/choirmaster at St Mary’s, Witney. I sing bass with Oxford Pro Musica Singers and the Cathedral Singers of Christ Church, Oxford.